Review of “How Informational Realism Dissolves the Mind-Body Problem” by William A. Dembski

For centuries great thinkers have wrestled to understand the relationship between the physical human brain and the nonphysical mind—specifically how consciousness, thoughts, and feelings interact with the material of the brain itself. This paper is a review of a new framework known as informational realism (IR) that brings together ideas from information technology to help explain how we are as humans: our minds and our very understanding of reality as created by an omniscient god. This framework of IR is presented in the final chapter written by Dr. William Dembski in a recent book, Minding the Brain. 1 Dembski is an author and a long-time advocate within the intelligent design movement. Dr. Dembski has PhDs in both mathematics and philosophy as well as an MDiv.

In this recent book chapter Dembski introduces and explains the IR framework by combining concepts both from the field of philosophy as well as the relatively young science of information theory. Although the author of this article is not a philosopher, he does have a background in communications and information theory.

Informational Realism as Related to Monism and Dualism

To present his framework, Dembski first reviews several different competing philosophical views of reality that both struggle to explain the phenomenon of human consciousness and its relationship to the body.

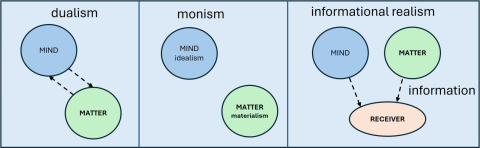

Dualism is the belief that mind and matter represent two different and distinct types of being. In contrast, monism is the belief that there is only a single type of being; Dembski treats both materialism and idealism as forms of monism for his discussion. In each of these three cases, Dembski believes that the view is unable to give a complete and satisfactory explanation of human consciousness, and this is where his proposed informational realism comes into play. There are several themes in Dembski’s chapter that he brings together through several stages of discussion with a good amount of background information for the layman:

- One primary goal is to define what is known as the mind-body problem—a failure to understand or explain the relationship between the human mind and the physical body.

- Second, Dembski brings elements of information theory into a philosophic framework—a relational ontology—to propose that reality is defined not by entities but rather by the flow of information from sources to receivers as the fundamental basis of reality.

- Finally, he explains how this IR ontology can explain our reality—its creation, existence, and how this can be consistent with a Christian or biblical worldview.

Figure 1 is a simple diagram that shows the different philosophical views that he uses to help define IR. This figure distinguishes between dualism, two different forms of monism (materialism and idealism), and also IR as the new framework that admits both mind and matter through the exchange or flow of information as we will explain below.

Another important characteristic of information realism that we shall see is its consistency with a biblical view of reality—both the reality of human consciousness and of our material world as well as their relationship with God their creator. God’s role as creator means that he is the ultimate source of information that flows into reality through his acts of creation.

Information and Information Theory

Before describing IR in detail Dembski explains at length what he means by the word “information.” Although we all have some basic understanding of information in our own lives, he presents specific understanding of information as the interplay between contingency and constraint. In this telling, contingency relates to the many different ways that things might be in the world. From the weather of any day to events occurring around us to the structure of the world itself, the many different possible ways that things “could be” are the contingencies that need to be resolved by information. Furthermore, gaining information about this contingent world is done by understanding constraints that exclude some of these possible outcomes of the world and include other outcomes. These constraints are information that help us understand how the world actually is or what events actually happened in reality.

Dembski goes on to explain how this contingency-constraint approach of information has become more useful in formal science and engineering through the development of techniques to quantify information using 2probability and to also enable computation by representing information as digital information, or bits. Dembski also makes it clear that information is not just dynamic rather than static but also is inherently relational information that flows from a source to a receiver.

This understanding of information is then used as a basis to understand the relatively young field of communication theory, also known as information theory. This field of study has developed over the last 80 years and is often dated from the work of Claude Shannon. Shannon’s primary work was his 1949 book, The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Shannon worked for Bell Labs at the time, and this book became the foundational work for engineers and designers to understand techniques to optimize the transmission of information that has led to our amazing modern information society. These technical capabilities have led to the growing field of telecommunications, where technologies from radios to cell phones to the amazing internet have interconnected the world today.

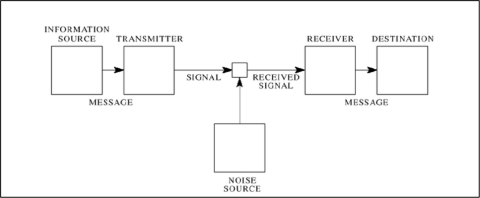

Shannon’s work included techniques to quantify information by measuring the amount of information in any set or sequence of symbols. It also focused on a canonical approach for understanding the communication of information over a distance. Figure 2 is taken from his work and shows information flowing from a source through a transmitter, then eventually being received and converted back into a message that is understood at the destination. Shannon’s theories of information and communication provided a clear approach that has motivated Dembski to extend this concept to the creation of informational realism that describes our reality.

Informational Realism

Using this deeper understanding of information and the formalization of information flowing from its source to its destination, Dembski now gives a more detailed explanation of what information realism is and how it sees the world. At its heart, IR is a different view of the world than conventional monism or dualism. It sees reality not as material objects or as ideas inside an abstract mind, but rather it holds that reality is derived from the flow of information from sources to destinations. As our own minds receive information from sending entities, they understand reality, and these entities actually become real. 3

It is not merely that information is real (in the sense of data or representation); rather, IR asserts that information-exchange is reality’s defining trait. When we receive information from other entities, the reality of things around us is established as we receive information about people and objects and events in the world. That information flows into our mind and constrains all the contingencies that are possible and helps us to understand what is actually real in the world around us. Returning to Figure 1, we see that IR supports the existence of both material and immaterial entities and indicates that these entities become real as they exchange information with us or other receivers in the world.

Because it defines reality through the exchange of information, IR keeps intact the objectivity of the external world; trees, rocks, and bodies exist, interact, and exert causal influence because these are informationally connected entities. At the same time, IR accounts for subjective, mental phenomena—conscious experience, information content and reasoning, and meaning—without resorting to “ghostly” nonphysical substances or mysterious emergent properties. The “mental” becomes just one aspect of informational relations.

Dissolving the Mind-Body Problem

The primary success and value of information realism is that it helps to resolve the mind-body problem and related challenges that come with other philosophical worldviews.

In Dembski’s telling, the mind-body problem is created by other worldviews, such as materialism, that artificially restrict the creation and flow of information. Materialism as a belief absolutely prohibits any information that would flow between an immaterial source such as a mind and a material body. The problem for the materialist is therefore to explain all the aspects of the conscious mind as results of material substance and processes alone. Other chapters in Minding the Brain discuss various lines of evidence for the immaterial reality of the mind. Decades of results from neuroscience and personal accounts of near-death experiences and other aspects of human consciousness defy materialistic explanations and understandings of human minds and consciousness. 2

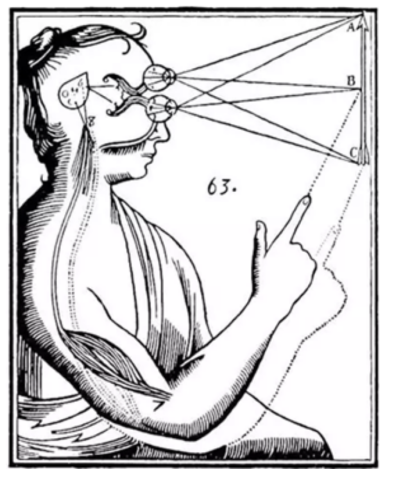

IR also “dissolves” the mind-body problem that flows from views such as dualism. Figure 3 shows an image from the work of René Descartes, father of Cartesian dualism, which posits that mind and body are two fundamentally distinct entities. Figure 3 shows Descartes’s attempt to illustrate a flow of information about the world seen through the eyes of an observer that is then somehow communicated with the observer’s mind that subsequently leads to interaction with the observer’s body and arm.

This form of dualism has led to the mind-body problem created by the difficulty in explaining how an immaterial mind can interact with or causally influence a material body or brain (or vice versa) that must somehow be observable in some material or mechanistic manner. Rather than positing, as dualism does, two fundamentally different substances—“mind (nonphysical)” and “body (physical matter)”, IR offers a unified metaphysical substrate: information. This sidesteps many problems of traditional dualism (e.g., how two such different substances interact).

It seems important to note that Dembski’s presentation of IR does not necessarily provide a detailed “mechanism” of how consciousness arises in brains; instead, it reframes the metaphysical ground. That is, it does not reduce mind to neuronal mechanisms but lifts both mind and matter to a more fundamental informational plane. Dembski concedes that additional evidence and inquiry would be needed to better understand flows of information and the capabilities of specific sources to produce or receive information.

God as the Ultimate Source of Information

What are the implications of the claim that information is the foundation of all reality? As Christians we already understand that God used information—his spoken words—to create our world. He created all matter from nothing, life from nonlife, and mankind with his body and soul (mind) as distinct from all other created beings. These beliefs align with the IR understanding of creation and existence; it is the flow of information from a sender—God in this case—to a receiver that accounts for the existence of any real entity.

Although it is not presented as part of informational realism, we also know that God is the source of the ultimate truth about Himself, about ourselves, and about the world around us, through His words conveyed through the Scriptures. He reveals Himself through both His words and His creation so that we know that He is real and so that we can give Him the worship that He deserves.

- 1Dembski WA, “How Informational Realism Dissolves the Mind-Body Problem,” in Minding the Brain: Models of the Mind, Information, and Empirical Science, eds. Angus J. Menuge, Brian R. Krouse, Robert J. Marks (Discovery Institute Press: Seattle, WA, 2023).

- 2Egnor M, “Neuroscience and Dualism,” in Minding the Brain: Models of the Mind, Information, and Empirical Science, eds. Angus J. Menuge, Brian R. Krouse, Robert J. Marks (Discovery Institute Press: Seattle, WA, 2023), 248.