Review of ”The Origin of Human Language Capacity: In Whose image?” by John W. Oller and John L. Omdahl

Introduction

This paper originally appeared as a chapter in a longer book entitled The Creation Hypothesis, edited by J.P. Moreland. 1 Although written 30 years ago, this paper and topic are still extremely relevant and have gotten more interesting over time due to advances in genetics and other scientific areas over the last several decades. In this paper, the original question discussed by the author was straightforward: Is language capability in humans an extension of animal cries and calls, or is it much more than that? In the paper, the authors lay out a case involving several different topics that we will review here. In particular, the authors conclude for a number of reasons that human language capacity is evidence of special creation in humans. In their telling, human language, due to its uniqueness across living systems that enable such versatile and abstract expression, is evidence of a “…supremely articulated special design” in humans.

From a biblical creation perspective, the answer to this inquiry is clear—our brains, minds, and our language itself are part of God’s creation, and that includes our abilities to communicate, learn, teach, and worship our Creator, as indicated in Figure 1—language is a part of what makes us human. Even our capacity for thought itself is a gift from our creator who made us in His image. In this paper however, the authors present a wide range of evidence and thoughts from numerous fields of inquiry, including linguistics, biology, and philosophy. In this review, we will highlight three main area of their discussion:

- First, according to eminent MIT professor Noam Chomsky, “the father of modern linguistics”) human language is a “…unique phenomenon, without significant analogue in the animal world.” 2 For this and other reasons, he and many other scientists have concluded that human language capacity is essentially innate—that the capacity is biologically “pre-loaded” in the human brain.

- Second, the authors discuss how language in humans is analogous to the biological system of information storage and transmission—DNA and RNA—that has been found to underlie all living organisms throughout the animal kingdom.

- Third, the original paper presents an extended discussion of how the words or word-combinations of human language manifest a correspondence between our abstract world of ideas and the external concrete world of impressions from our senses. The unbridgeable gulf between these two domains has amazed some of the greatest minds in science and philosophy.

In this review, we will describe these three different lines of evidence to provide a sense of the authors’ overall case about the original source of the human language capacity. As an additional note, these same discussions have appeared in similar form in more recent publications by these and other authors, but in this original chapter the authors provide a single work that brought together these disparate ideas to support single conclusion.

Language: Unique to Humans and Innate in the Human Brain

One key consideration discussed in this paper is the degree to which human language capacity is essentially unique with respect to all other communications within the animal kingdom.

As part of this discussion, the authors address the question of whether apes can acquire human language capabilities. Although the answer to this question seems obvious to us today, past scientists spent significant time to investigate this question. As this paper was written in the 1990s, the authors were able to review several decades worth of work where scientists and linguists had attempted to teach chimpanzees and other primates to acquire and use language. They review several different experiments that took place in the 1920s and 1930s and on through the 1970s where scientist tried to teach apes—chimpanzees, or in one case a baboon—to use sign language or even a special keyboard system to communicate with language. Although the claims of the resulting ape capabilities from these experiments were often touted as true language, other scientist remained skeptical that it demonstrated anything very much akin to a real language capability.

The authors detail several specific aspects where the apes’ capabilities fell far short of human language in these experiments. Although the apes could acquire a vocabulary of several hundred different gestures or keystrokes after years of continual training, they never were able to display any evidence of abstract thought. One of the key features of true language is that the structured combinations where different words can be mixed and rearranged to create an infinite number of different meanings for a finite set of words symbols. This was entirely lacking in the animal experiments. Although animals could use their vocabulary to talk about objects in their immediate environment, these were never really strung together or combined to convey abstract thoughts. Another noticeable item missing was the ability to ask questions or to use other “rule-governed arrangements” of words that are universal in human languages. The authors relate how the ability of any normal human child to rapidly learn any language with relatively sparse data was far beyond any animal achievement and still defies explanation. This is the key evidence—rapid language learning—that has led many modern linguists to conclude that language capacity is essentially “built-in” as part of the human brain. This innate language processing capability allows children to learn any of the world’s 5000-plus languages based on only 36 to 60 months experience. None of the apes studied could do anything remotely like this.

As mentioned earlier, this miraculous capability of any normal human child is what led Chomsky—the foremost language scientist of the twentieth century—to conclude that human language capability is innate within the human brain:

Some intellectual achievements, such as language learning, fall strictly within biologically determined cognitive capacity. For these tasks, we have “special design,” so that cognitive structures of great complexity and interest develop fairly rapidly and with little if any conscious effort. 3

Despite their clear skepticism about real design in humans, Chomsky and many colleagues conclude that innate brain capabilities are the only explanation for human language capacity.

The Analogy of Human Language and the Biological Language of DNA and RNA

A second key point of the paper is the idea that human language forms and capabilities are a close analogy to the biological DNA system that is used to specify information in living systems. The authors describe DNA (as understood in the 1990s) and how the information system defined by DNA is used to represent and store information about protein structure inside of living systems. These specific DNA sequences, the genes, encode amino acid sequences and this information is then used to transcribe DNA to construct proteins that form the structures of different cells throughout the entire system of living organisms. The requirements for this system are to accurately store and retrieve information just as language can be used to encode, store, and retrieve information about concepts in the world.

Although the authors identified this analogous relationship between DNA and language in their paper as evidence of “design,” it’s clear that for some critics this analogy was somewhat weak and convincing. For example, one critique by philosopher Graham Oppy felt that this analogy didn’t really support the claim that human language capability must be a feature of intentional design or some special creation process. Over the last few decades, however, our understanding of DNA has become much more sophisticated. For example, although the original authors talk about DNA as an information storage and retrieval mechanism, genetic research today shows us that it is far more than that. We now understand that there are multiple forms and types of DNA and RNA that are used to not only encode proteins structures, but also to control and regulate internal systems and to enable the flow of information both inside and between organisms. RNA has several forms that both translate codes into proteins but also pass information back and forth to allow control of the genes and their expression. These different forms of RNA such as transfer RNA and messenger RNA allow the organism control processing and operate in a dynamic changing environment. 4

This deeper and continually growing understanding reinforces the original claimed analogy by the authors. We see now that this analogy involves not only the parallel functions of DNA/RNA and of human language but also their inherent nature. The fundamental nature of each—human language capacity and DNA/RNA coding—to the underlying organism implies that they are both intrinsic to the underlying organism implies that they are both intrinsic to biological life and to human communications and intelligence—as we will see shortly. In addition, each of these information-storage and information-transmission systems not only pass information back and forth between organisms and different parts within each living system, but they allow for information preservation and flow down to subsequent generations of organisms and human minds across succeeding generations.

The Unbridgeable Gap Between the Abstract and Concrete Domains

The authors begin their discussion of this “unbridgeable gap” by recalling the early speculations of Charles Darwin himself on the origins of human language. In his writings, he supposed that this capability was the result of some process where the natural sounds and imitations of other animal voices and cries led over time to the formation of human language. Despite this speculation about language as a gradually evolving capability, Darwin also firmly believed that human language was a key enabler and fundamental to human intellect: he said, “A complex train of thought can no more be carried on without the aid of words, whether spoken or silent, than a long calculation without the use of figures or algebra.” 5 He believed that human mental powers, like human language capacity, must have developed in many little steps over time.

More recently, the science of linguistics has developed as deeper study has worked to clarify the nature of human language—as well as detailed aspects in other related fields of psycholinguistics and biolinguistics. Over this period, science has come to a much deeper appreciation of not only the complexity of language but also the deep connection between language and intelligence—as well as with life itself. The authors specifically discuss Alfred Binet and his study of the connections between language and intelligence who said: “One of the clearest signs of awakening intelligence among young children is their understanding of spoken language.” 6 Also, the authors discuss at length the work of American scientist and philosopher Charles Sanders (C.S.) Peirce. His work drew on the fields of grammar, logic, language, and rhetoric; and he developed the field of semiotics, which is the study of representations. Pierce’s vast work—which is still to be fully understood by many—was credited by Chomsky as the primary inspiration for his own work and approaches in linguistics.

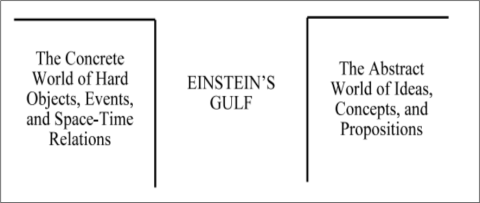

Finally, the authors also describe the conclusions of physicist Albert Einstein who also understood and marveled at the way in which all human thinking and even science entirely depends on our ability to link abstract concepts and analysis back to concrete sensory impressions from the world of experience. They present a simple picture that depicts what they term “Einstein’s Gulf.” Figure 2 depicts this fundamental separation between the concrete world of our sensory experiences and the abstract world of ideas and concepts that defines our very existence as human beings. Although the discussion is long and complex, the essential point is that Einstein and many others have come to believe that there is a fundamental link between language and thinking itself that is required to provide meaning to any intellectual activity.

Despite this fundamental link, Einstein could not account for how that bridging of the gulf performed by language was created or came to be:

The very fact that the totality of our sense experiences is such that by means of thinking (by the use of concepts, and the creation and use of definite functional relations between them, and the coordination of sense experiences to these concepts) it can be put in order, this fact is one which leaves us in awe but which we shall never understand. It … is a miracle. 7 8

Conclusion

One remarkable point that the authors make is that if the human language capacity is innate, then it is built into the human brain. Since that the human brain is specified by the language-like mechanisms and encoding of DNA then our conclusion must be that the human language capability itself must also be specified in the human genome that defines the proteins and structures of all the organs and systems inside our bodies. This implies that we have several nested layers of language, where the creator of human language capabilities has used the language of DNA to specify and encode an amazing system in our human brains that allows humans both to think and to communicate with all the richness of human language.

So now we see a series of conclusions that the authors bring together for their thesis. We see the incredible richness and complexity of human language systems that is innate in us and unique relative to anything in the animal kingdom. The authors also conclude that this capacity for language bridges that logical gulf that separates mind from matter—a gulf that cannot be crossed without the intervention of a truly transcendent intelligence. They thus answer their final question, “In Whose image?”—it is in the image of God.

- 1Oller JW, Omdahl JL (1994) Origin of the human language capacity: In whose image? The Creation Hypothesis: Scientific Evidence for an Intelligent Designer, ed. JP Moreland, Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL

- 2Chomsky N (1975) Reflections on Language, Pantheon Books, New York, 67–68

- 3Chomsky N (1975) 27

- 4Melchor A (2024 Sep 16) Cells across the tree of life exchange ‘text messages’ using RNA. Quanta Magazine, https://www.quantamagazine.org/cells-across-the-treeof-life-exchange-text-messages-using-rna-20240916/ Accessed 2024 Oct 21

- 5Darwin C (1874) The Descent of Man, Second edition. D. Appleton, New York, 88

- 6Binet A (1911) New investigation upon the measure of the intellectual level among school children. L'Annee Psychologique 1911:145–201. Reprinted in Binet A, Simon T (1916) The development of intelligence in children (The Binet-Simon Scale), trans. ES Kite, Williams & Wilkins Co., 274–239

- 7Einstein A (1936) Physics and reality. J Franklin Inst. 221(3):349–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-0032(36)91047-5 Accessed 2024 Oct 24

- 8Oller JW, Jr., ed. (1989) Language and Experience: Classic Pragmatism, University Press of America, Lanham, MD, 5